In the 1989 film Field of Dreams, Burt Lancaster plays the pivotal character Moonlight Graham. In the novel Shoeless Joe, upon which the movie is based, author W.P. Kinsella captured the complex frustrations of a man who came achingly close to achieving a dream to play in a major league baseball game. The real-life Moon Light Graham played the top half of the ninth inning for the New York Giants on June 29, 1905. He played right field without recording a putout or assist. The game ended with him on deck awaiting his only shot to enter the record books.

According to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), approximately 2,200 players have had similar experiences to Moonlight Graham. One such player is Stan “Stush” Ferek of Carmichaels. When I wrote my book on the history of sports in Greene County, I missed Ferek as an actual major leaguer for two reasons. First, although he was a longtime resident of Carmichaels, he was born in the Fayette County coal-patch of Keisterville. Therefore, he wasn’t listed as a Greene County native. More importantly, he was not recorded as a major leaguer due to circumstances that make Moonlight Graham seem lucky.

After graduating high school in 1940 at the age of 17, Ferek pitched for Keister against grown men in the highly competitive Big 10 coal mine league. He was a 6’1”, 180-pound lefthander with a devastating curve ball. In 1941, he tore through the league, posting a 35-0 record, which captured the attention of several scouts. His only loss that season was against the legendary Homestead Grays in a barnstorming exhibition at South Union Stadium. The Tigers and Pirates both offered him contracts, and he chose to sign with the local team.

The following season, he reported to the Pirates’ Class D affiliate the Oil City Oilers of the Pennsylvania State Association. His contract was for $500 and free room and board. After posting a winning record that year, promotion seemed inevitable. However, Ferek did what many young men of that era did. He answered a higher calling and enlisted in the Marines the day after the last game of the season. No doubt, the selflessness of that generation is enshrined in our history and may never be witnessed again.

He spent the next four years of his prime athletic life in the Pacific, island hopping and participating in historic battles. He took part in the invasion of the Marshall Islands, Saipan (where he was wounded in the knee and finger), Tinian, and Iwo Jima. He was also in Japan after the surrender. Ferek performed his duties with the same stoic resolve men of his generation assumed were part of the covenant of being an American. According to his son, Ron Ferek, his father never complained about the missed baseball opportunities. In characteristic fashion, the war-time tales of glory were never part of their family lore. In fact, they remained obscured until a trove of photos emerged from “Stush’s” attic after his death. One of those grainy photos was of the actual flag raising ceremony at Iwo Jima.

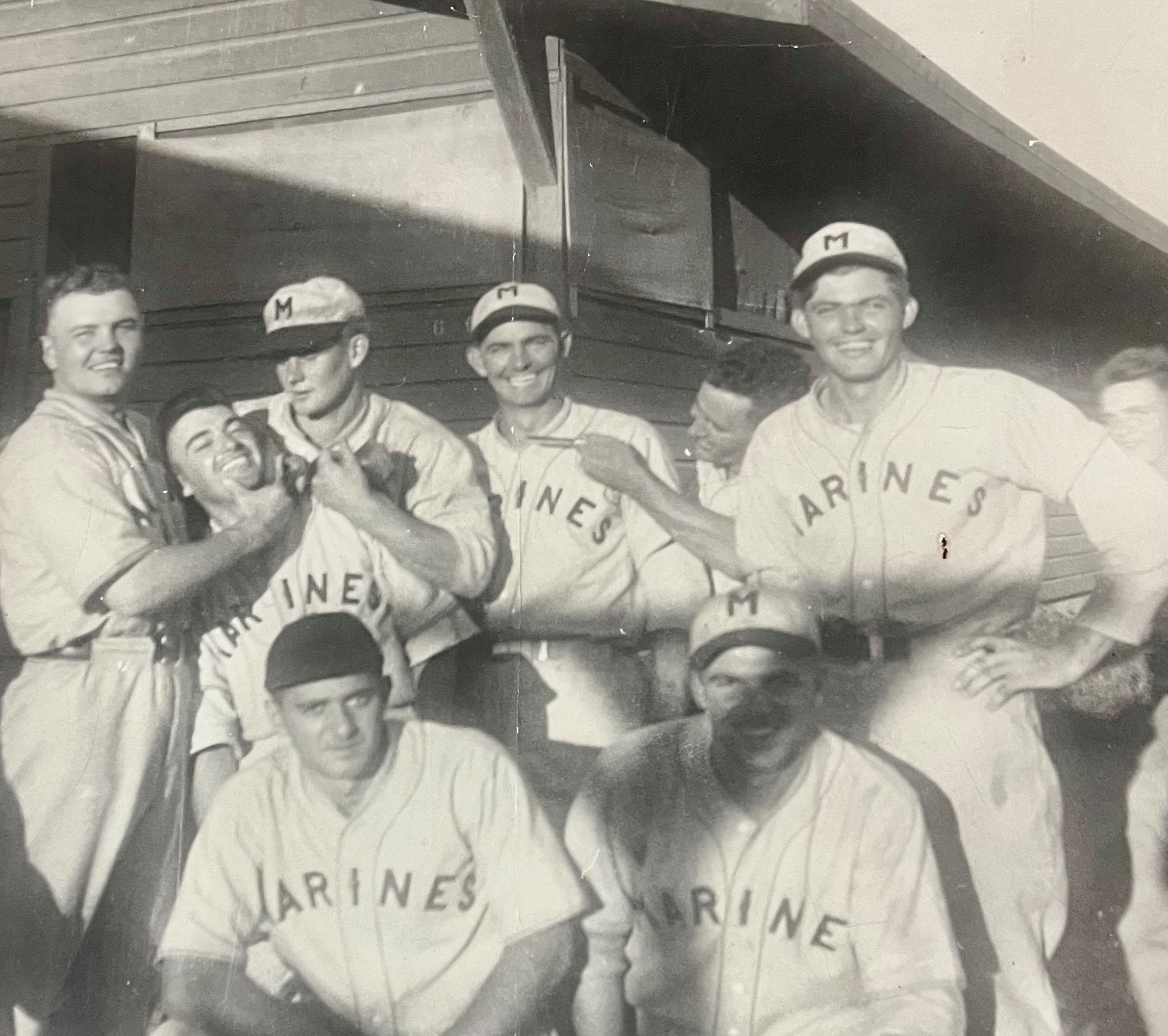

Before the Island campaign began, the troops were training and awaiting deployment in Hawaii. Baseball was one of the rare entertainments available to the soldiers and the locals. Thousands of spectators would turn out to watch teams representing various branches of the service face off against one another. The level of competition was intense given the quality of the players. A Honolulu sporting goods store sponsored the Williams Equipment Player of the Week Award. In early March, Ferek received the award after tossing a no-hitter against a Coast Guard team. A month later, a guy named Joe DiMaggio won the same award. In July, Dodger legend and Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese was the recipient.

After the war, Ferek returned to the Pirates farm system in 1946 and worked his way up from Class B Selma to AAA Indianapolis in only two seasons. In spring training of 1947, he had a tremendous outing against the Yankees. He impressed all-star Frankie Gustine and his camp roommate Danny Murtaugh with his tenacity when he drilled several Bronx Bombers and pitched 10 strong innings against starters during the exhibition game. He and Murtaugh would become life-long friends.

Ferek made the 1948 opening day roster, but had developed elbow trouble after his extensive use again during spring training. In June, the Pirates finally sent him to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for surgery. However, a nerve was partially severed, and he was never the same. He tried an unsuccessful rehab assignment back at Indianapolis. The following year, the team sent him back to A ball in Albany. However, after a couple of tough starts, he decided to retire.

He returned to Carmichaels and opened an Atlantic Service station in 1951 with the help of the Pirates. Atlantic Refining had been a long-time sponsor of the Bucs. Murtaugh and a group of his old Pirate buddies showed up to promote the grand opening.

Always a good hitter, Ferek ended up playing first base for the Nemacolin team in the Big 10 league. He was elected to that league’s hall of fame in 1971. He remained involved in the game by coaching the Carmichaels legion teams in the 1960s. However, Ferek’s first love (after his wife Blanche) was playing trumpet and leading his renowned polka band, Stush and the Boys, for a quarter century at various wedding and party venues around the area.

In Field of Dreams, Kevin Costner’s character asks Moonlight Graham how he can live with the “tragedy” of not fulfilling his dream to bat in the major leagues. Graham replies it would have been a “tragedy’ for him not to become a doctor. The other thing was just an unfulfilled wish. The depth of understanding and maturity of that character’s response is emblematic of Stush Ferek’s generation. A generation that knew that family, friends, community, and country are the truly important things.