Coming south into Blacksville on State Route 218 is a sharp right curve into history that once had no line dividing Penn’s Woods from Lord Calvert’s Virginia Colony. That curve is where a fortified cabin once guarded the high ground above Dunkard Creek. When John Baldwin built his blockhouse in 1774, the British were hiring Indigenous tribes to join the skirmishes that would soon become the Revolutionary War. Raiding parties would send settlers fleeing to the blockhouse for the next 17 years. The original tribes that once built villages and farmed these valleys for hundreds of years were long gone – this wilderness was now the dividing line between French and English colonization and haunted by the displaced tribes of the East being driven westward. The nearby Warrior Trail that crosses Greene County made this land a strategically dangerous place to settle but those who came to settle persevered.

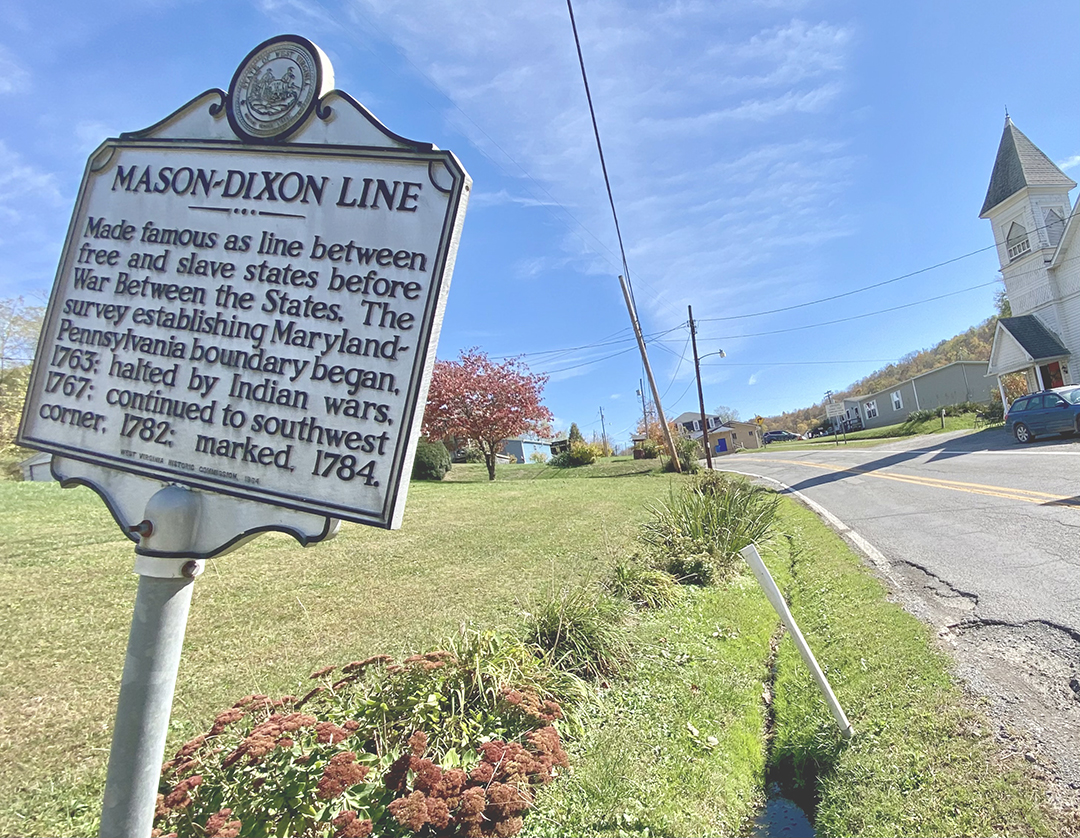

Eugene Lemley lives almost on the spot where the blockhouse is said to have been. Heavy yellow posts guard his front porch from the traffic that sometimes makes that sharp curve into West Virginia too fast. A heritage road sign proclaims this is the Mason-Dixon Line and the date of its completion – 1782 – helps explain why frontier farms and houses tend to sprawl on either side of what would one day be a state line.

Eugene Lemley lives almost on the spot where the blockhouse is said to have been. Heavy yellow posts guard his front porch from the traffic that sometimes makes that sharp curve into West Virginia too fast. A heritage road sign proclaims this is the Mason-Dixon Line and the date of its completion – 1782 – helps explain why frontier farms and houses tend to sprawl on either side of what would one day be a state line.

The first known settlers in this area were Brice and Nathan Worley and William Minor, who made their claims in the years before the Mason-Dixon survey reached Browns Hill in 1767, then turned back because of the proxy war being waged on the western frontier.

Brice Worley’s land title, granted by William Penn, met that of Alexander Clegg on the dividing ridge above Dunkard Creek. The strip of unclaimed land between them became a place for “squatters” who cleared land, built cabins and settled into hard frontier living. When John Baldwin built his blockhouse, the community that formed around it called itself Hampshire Town. When Virginia civil engineer John Black arrived in 1800, he too built a cabin, then later bought 160 acres along with the squatters’ rights in Hampshire Town and laid out lots. In 1830 Blacksville was born.

Eugene’s house sits beside Blacksville United Methodist Church on the short straightaway before Route 218 – once known as Lafayette Street – takes another hard right down to State Route 7, or muddy, rutted Washington Road if you jump back a century or two.

Eugene’s house sits beside Blacksville United Methodist Church on the short straightaway before Route 218 – once known as Lafayette Street – takes another hard right down to State Route 7, or muddy, rutted Washington Road if you jump back a century or two.

Eugene has The Blacksville Story, a book that tells all of this and more. It’s beautifully laid out, full of photos and oral histories gathered by lifelong resident Sara Isabelle Scott (1910-1995) and put in a timeline from frontier days to 2003 by West Virginia historian Norma Jean Venable. I was thrilled to find it still available for sale at Clay-Battelle Library.

After the Revolutionary War, the frontier slowly turned to farmland, big game disappeared and sheep took over the cleared hillsides. Circuit riders undoubtedly passed through and John Black was known to be a Methodist. When he laid out the town he offered a free lot and $75 to the first church to open there. In 1851 the Methodists took him up on it.

African slaves passing through Blacksville while it was still part of Virginia were helped along their way to Canada, by all accounts. When West Virginia became its own state in 1863, a number of families sent their sons to serve in the Union Army.

Norma Jean tells us that after the Civil War, Blacksville fell in love with steam engines and built a new gristmill with roller mills from Europe that produced fine flour. The first big oil strike of 1888 brought in drillers, teamsters, rig builders, tool fitters and roustabouts for the boom times, along with a love story that still survives as a truly philanthropic endowment for arts, the humanities and social improvement.

The oil boom of the 1890s brought a young Mike Benedum to town to procure oil leases and the John Lantz family was taking in boarders. Mike fell in love with their only daughter Sarah and they married in 1896. When the kid from Bridgeport, WV joined forces with young engineer and geologist Joe Trees, Benedum began earning his title as “The Greatest Wildcatter.” Mike and Sarah lived in a mansion in Pittsburgh but never forgot their roots. In 1944 the couple created the Claude Worthington Benedum foundation in memory of their only son who died of influenza while serving in Europe in 1918. The foundation still has the “flexibility and funds to benefit the people of West Virginia and Western Pennsylvania in perpetuity.”

Someone back at the turn of the last century had an eye for beautiful everyday things. I’m startled to see women on horses riding astride in flowing skirt-pants, grinning for the camera, to see Louverna Tennent and her family posing with their flock of sheep, to catch passenger trains pulling through Blacksville in the 1920s carrying passengers from Brave to Morgantown and back. Oil derricks pop up in backyards, trestles are built for bridges across Dunkard Creek, kids go fishing. These family photos capture the spirit of the day as time brought changes and people persevered. State Route 7 was finally paved in 1929 but the fastest way go get out of Blacksville any time of the year was by train. Thanks to that train, students could get to college in Morgantown and Fairmont and bring their learning home as educators, innovators and community leaders.

With the Great Depression, help from the Federal Government took the form of WPA projects, including a town cannery where the community could process USDA food to feed neighbors, school kids and the elderly. When a natural clay deposit was found on Simeon Lemley’s farm in 1937, the Smith Hughes Act helped set up a pottery business to teach seniors how to start in-home businesses. Many residents learned to make pottery, both on the wheel and by coiling. Later it became part of the curriculum at Clay-Battelle High School. At one point, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was presented a “fine tea pot with a special Eleanor blue glaze” by school superintendent Floyd Cox.

For as many times as I’ve come to Blacksville, either for check ups at the state funded clinic before Cornerstone Clinics were organized in Greene County, or passing through on my way to Mason-Dixon Historical Park in Core for a festival or a feast of spring ramps, this is the first time I’ve slowed down and appreciated the history tucked into every old building, some restored as a bank, a grocery store or an historic home. Thanks, Eugene Lemley for telling me the story of your family!

When I stopped by Clay-Battelle Library after visiting with Eugene to buy my own copy of The Blacksville Story, librarian Sandra Throckmorton told me that the library was built in 1974. Back then, Federal funds were available to upgrade communities in rural America, and those savvy enough to write the grants to get those improvements reaped the benefits.

“We have extra copies,” Sandra tells me. I assure her that I’ll tell everyone I know that this book is now available for $10. All proceeds go to the library so stop by and pick one up!