By Colleen Nelson

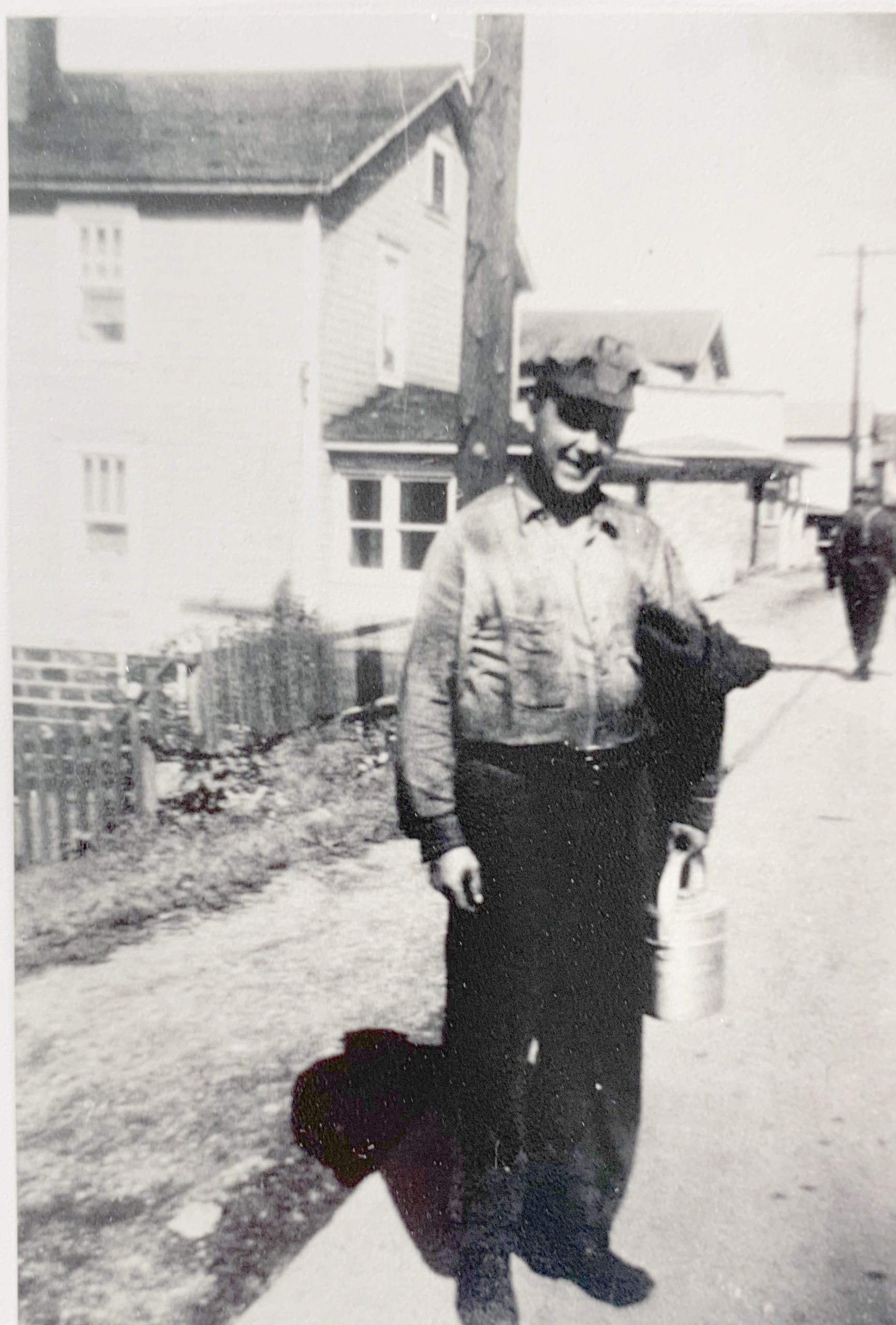

This is a photograph of Linda Rush’s grandfather, Anton Maurin, standing in Serbiantown and, by the looks of his clothes, is just coming off a shift. The year is sometime in the early 1940s, at the start of World War II and Anton is working at Crucible Mine. His job wasn’t as dangerous as it once was, but Anton had already lived through the days when miners were forced to fight for better working conditions and better pay and were met with sometimes deadly resistance as they went on strike and organized to get these concessions from the companies they worked for.

“Grandpa Maurin was extremely hard core UMWA. He was shot on the picket line at Gates Mine in Fayette County in 1933 and died with bb’s in his legs,” Linda notes. Anton survived that picket line to live another handful of decades and even managed to hang on to life for an extra three days during his last illness, Brice Rush tells me, long enough through sheer will power to die in 1981 on April 1 – Mitchell Day. At the time of Anton’s death, it had become a celebration of the day in 1898 when the United Mine Workers of America won the rights to a 40 hour work week and the 8 hour day. This hard won concession would in time become the standard for all working people of America. The struggle would continue for decades as industry fought back and miners and the UMWA responded in kind, organizing, unionizing and striking for the rights of the American working class to live the American Dream.

John Mitchell (1870-1919), a second-generation Irish immigrant, worked all his life in the coalmines, starting at age 6. He became one of the founding members of the United Mine Workers of America in 1890 and rose through the ranks to affect real change in the deplorable working conditions of the turn of the last century.

One of Mitchell’s earliest victories was uniting new immigrants from various nationalities into a union force to be reckoned with, helping them overcome the language barriers and social prejudice they faced. When he became the fifth president of the UMWA in 1898, Mitchell inherited the fallout from the Lattimer massacre when 19 miners were killed by police. He became a contentious negotiator when President Teddy Roosevelt intervened in 1902 and forced the anthracite coal industry to concede to a minimum wage and safer working conditions after a six-month strike. Union membership grew from 34,000 to 300,000 during Mitchell’s time in office and miners celebrated his tenacity with a yearly shout out even as they continued the struggle for safer working conditions, better hours and better pay.

One of Mitchell’s earliest victories was uniting new immigrants from various nationalities into a union force to be reckoned with, helping them overcome the language barriers and social prejudice they faced. When he became the fifth president of the UMWA in 1898, Mitchell inherited the fallout from the Lattimer massacre when 19 miners were killed by police. He became a contentious negotiator when President Teddy Roosevelt intervened in 1902 and forced the anthracite coal industry to concede to a minimum wage and safer working conditions after a six-month strike. Union membership grew from 34,000 to 300,000 during Mitchell’s time in office and miners celebrated his tenacity with a yearly shout out even as they continued the struggle for safer working conditions, better hours and better pay.

I drove the three plus miles from Carmichaels to Crucible and then down the hill past the defunct Crucible Mine to Serbiantown to see for myself the neighborhood that was once an ethnic enclave. Now it is a short row of homes, some remodeled, some waiting for the right family to come forth, along the banks of the Monongahela River, overlooking overgrown fields where Crucible Mine once spread its industrial profile across the land.

It doesn’t take an artist’s eye to see the potential here. Industry is gone and what is left is the beauty of a river front town, waiting for new owners who will appreciate the low housing prices and the rails to trails that has made it to Serbiantown and will one day connect to Point Marion.

Like the once industrial South Side of Pittsburgh, these parts of Greene County are waiting for those with the vision to transform them into industrial parks and affordable housing for the workers that will come looking for a better life.

Times change. But the river is still as beautiful as it was when the Shawnee named it “Mehmonananagehelak.”