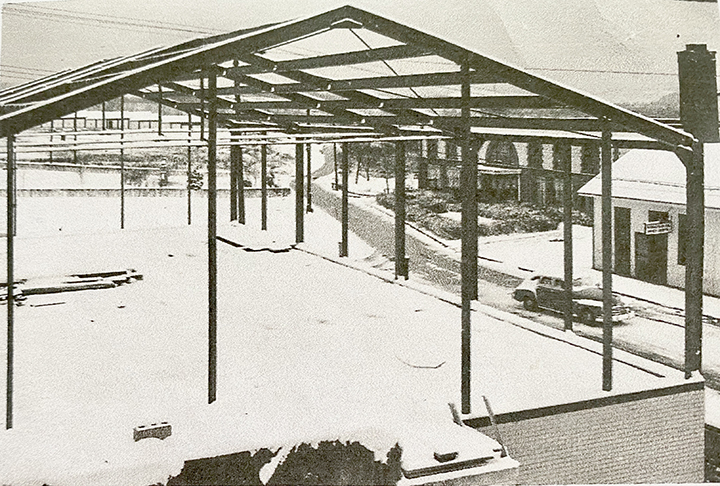

This photo is a point in time to remember – It’s 1950 and Nemacolin’s new UMWA headquarters on Pershing Boulevard is under construction. The basement that will someday house the post office is already done and the steel girders of the walls and roof frame the center of town. It’s a snapshot in time that will soon be gone – the old post office in the company parts store building burned in 1961 and the Nemacolin Supply Company store in its heyday, complete with decorative shrubbery.

“I like the old car,” UMWA 6290 Financial Secretary Skip Homerock says as I take a look at the photos he brought and realize this one is the perfect blast from the past to write about. What better image to show the strength and tenacity of a coal town than a photo of its union hall being built?

I’m sitting upstairs in that same building, ready to listen to three retired miners talk about all things coal. Skip gets me a Dr. Pepper and we settle in to swap enough stories to fill a book.

Recording Secretary Bruce Black got to Buckeye Mine in 1974, after three tours in Vietnam. He points to the photos on the wall and chuckles. “Those used to be the old timers when we started. We’re the old timers now.”

Much of today’s UMWA focus is on protecting pensioners. Many have black lung and all need the security of a pension and quality health care. I was on the ride to Washington D.C. in 2016 when 20,000 miners and their families arrived, not to talk politics but to stage a bipartisan rally to ask congress to protect their pensions and health insurance.

Much of today’s UMWA focus is on protecting pensioners. Many have black lung and all need the security of a pension and quality health care. I was on the ride to Washington D.C. in 2016 when 20,000 miners and their families arrived, not to talk politics but to stage a bipartisan rally to ask congress to protect their pensions and health insurance.

“We won that one,” president Adam McKean says with a huge smile.

Bruce – “Blackie” to anyone who worked with him in the mine – speaks the language of coal – cage, fire boss, motorman, power switch, emptier, motor barn, second south – as he describes life in the rooms and passages and miles of track that made up Buckeye Mine when he and Adam went underground as white hats. I have a hard time wrapping my head around the many directions this rock dusted world took with its sections of tunnels leading to the face of the coal being cut, loaded and hauled out. I’m suddenly eager to come back and hear more, to document this story while those who lived it are still here to tell it.

Later, as we tour the many photographs, UMWA charters, signs and accolades that fill the walls I’m delighted to spot a framed photograph of my neighbor Rosanna Lane standing with a group of mine buddies. Women won the court case that allowed them to work underground in the late 1970s and Rosie was one of the first to wear a hard hat and work at Buckeye Mine until it closed in 1986.

“I worked with all the women miners when they came in – Rosie, Mary, Carol, Sherry Janie, Mary Jane, Aldine…. They were good; they wanted to learn. Tell Rosie Blackie said hi!”