For well over a century, local historians have been recording and preserving our local history. The earliest newspapers, documents and publications up to the present day have kept a running account on what makes us who we are as a people and keep the story going of what life has been like in this rural region in southwestern Pennsylvania.

In the early 1930s, a man from Topeka, Kansas by the name of William F. Horn began writing to the editors of newspapers in Greene and Washington counties, sharing with them what seemed to be items of great historical interest. Between 1932 and 1936 dozens of articles and columns appeared throughout the region that thrilled many of the area’s historians with their seemingly complete 18th century account of the settlement of western Pennsylvania.

Greene and Washington counties have extraordinarily rich and interesting histories and the articles by Horn began to fill many of the gaps in the previously recorded narratives. Horn said he was referencing material handed down through his family that had allegedly belonged to his ancestor, and western Pennsylvania pioneer, Jacob Horn.

The documents covered a period between 1765 and 1795. Some locals had their doubts about the material Horn presented, but in 1936, Horn unearthed several lead plates buried in locations mentioned in his documents and most of those doubts were cast aside.

The lead plates were purported to have been left behind by early explorers as a record of their presence and a claim to the land. This was not an unprecedented custom in the frontier days. Many early explorers left behind lead plates in the Upper Ohio Valley throughout the late 17th and 18th centuries.

The lead plates were purported to have been left behind by early explorers as a record of their presence and a claim to the land. This was not an unprecedented custom in the frontier days. Many early explorers left behind lead plates in the Upper Ohio Valley throughout the late 17th and 18th centuries.

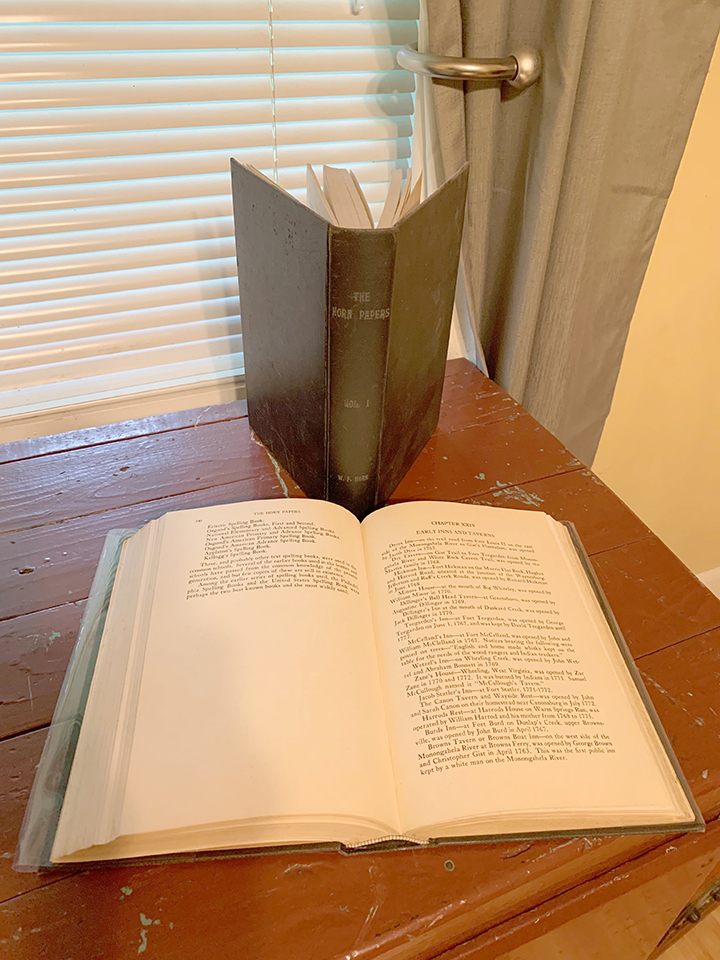

By 1945, after a few interruptions by World War II, Horn had moved to Waynesburg and the Horn Papers were being printed in a three-volume book set, available for the pre-subscription price of $20 and $30 after printing.

The stories contained in the Horn Papers shed new light on many of the mysteries surrounding the “dark ages” of early western Pennsylvania. Few records were kept during the 18th century in this region, and even fewer records survive. Now new light had been shed on this interesting period in American history, but that light would later prove to be artificial.

Publication of the sensational Horn Papers set them upon a national stage, and it was not long before they were exposed to serious academic scrutiny. Universities and historical institutions all over the country, specifically a few notable scholars from William and Mary University in Virginia, conducted an examination of the original documents, and proved that the Horn Papers were a farce.

Later, a report published in 1946 by a committee of scholars from the historical societies of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, and West Virginia found that there were “evidences of ineptitude in copying original documents anachronisms and doubtful words and phrases, biographical anomalies, historically incorrect or doubtful statements, internal discrepancies,” and “internal similarities of documents purporting to be of different authorship.”

A second phase of investigations showed that “[t]he documents and maps were not from 1760-1800 as claimed, but much later, one person produced all items examined,” and “the ink used in the documents show they were written no later than 1930.” The lead plates produced by Horn were the final factor that determined the inauthentic nature of the Horn Papers.

The plates, when subjected to spectrographic analysis, showed that they were made from a type of lead present in Missouri that would not have been available in western Pennsylvania in the 18th century, but would have been readily accessible in Topeka, Kansas in the 1930s. The story was ultimately covered in most of the academic journals of the day and was even featured in Time Magazine in November of 1947.

So, what does that leave us with? Three volumes of very dubious history? Well, that’s only partially true, about two-thirds true to be more exact. Volume three of the Horn Papers, the atlas volume (which incidentally does NOT contain maps from William F. Horn), contains the original Land Patent Maps for Greene, Washington and Fayette counties. These maps would likely have never been published in book form were it not for the printing of the Horn Papers. Volume three is a treasure trove of historical and genealogical information. Township by township of the three counties, it lists, in the form of incredibly detailed maps, all the original landowners in southwestern Pennsylvania.

So, what does that leave us with? Three volumes of very dubious history? Well, that’s only partially true, about two-thirds true to be more exact. Volume three of the Horn Papers, the atlas volume (which incidentally does NOT contain maps from William F. Horn), contains the original Land Patent Maps for Greene, Washington and Fayette counties. These maps would likely have never been published in book form were it not for the printing of the Horn Papers. Volume three is a treasure trove of historical and genealogical information. Township by township of the three counties, it lists, in the form of incredibly detailed maps, all the original landowners in southwestern Pennsylvania.

I leave you, the reader, with a word of advice – be wary of volumes one and two of Horn, for there are tidbits of accurate information in there. Any student of local history eventually learns that in many places Horn differs from the other noted historians like Evans, Hanna, Bates, Waychoff, Lecky and others, and there is a reason for that. Horn’s information was one of the greatest frauds in history.

No one has ever been able to determine why William F. Horn spent what must have been years assembling all his “information.” Shortly after the report was published in 1946, Horn returned to Topeka, Kansas where he died in obscurity in 1956. There were rumors, after investigations uncovered the Horn fraud, that Horn did in fact have records and documents as he described, but they were destroyed and he recreated them from memory and notes.

Within the Horn Papers can be found accurate bits of history. It is advised against trusting their content or using it as source material unless you are prepared to go the distance and verify the information from other sources, and that can prove difficult.

Horn, for instance, describes the burial place of a Robert Morris (an early pioneer of Greene County) correctly, where nearly every other historian got it wrong. Horn describes his grave on a hilltop on the original Morris farm, just east of Waynesburg. Other sources claim he is buried in the Rhodes Family Cemetery in Franklin Township. The location of Morris’ grave can be verified by surveys conducted in the early 20th century by the Works Progress Administration that show the grave exactly as Horn describes it.

Regardless of Horn’s motives, the great hornswoggle of Greene County history has left its mark, and is an unusual chapter in the history, and study thereof of the early frontier. Always ensure while researching, even when looking in books not written or compiled by Horn, that the Horn Papers were not used as source material. Lack of knowledge about Horn and his fraud have tainted many sources that scholars and historians still come across today.